| Hochdruck/Künstler a - z |

| Grafik außer Hochdruck |

| Illustrierte Bücher/Künstler a - z |

| Ephemera |

| Mappenwerke |

| Zeitschriften |

| Druckstöcke |

| Objekte |

| Junge Kunst |

| Neuerwerbungen |

|

Franz Part |

|

22.9.-25.11.2022 |

|

Ort: Galerie Hochdruck, Friedmanngasse 12/5, 1160 Wien |

||

|

||

|

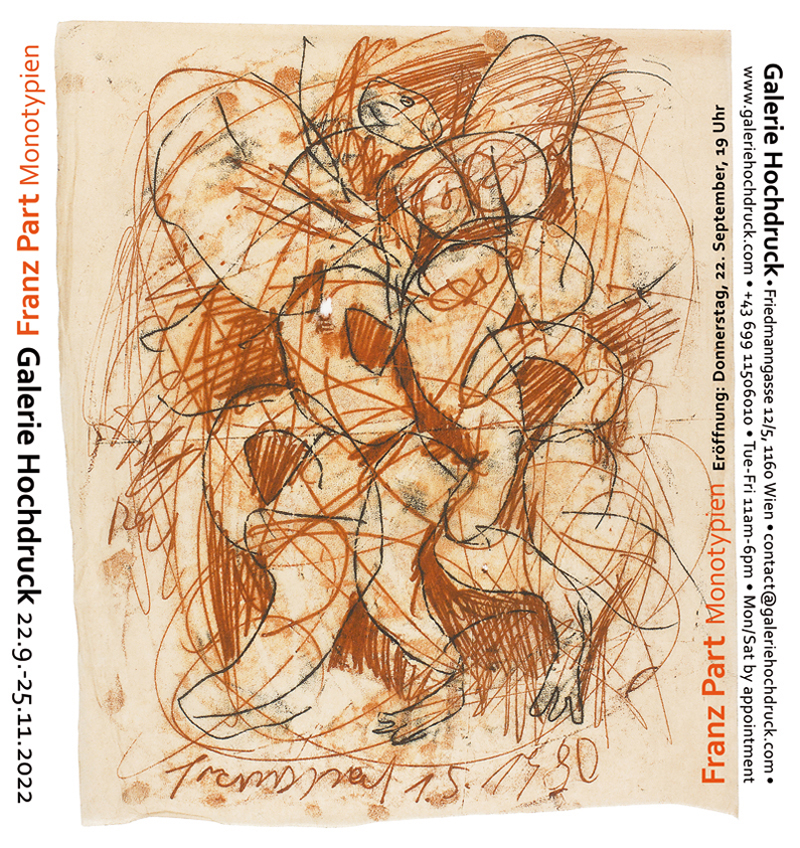

Über den Künstler und Pädagogen Franz Part kann man in zahlreichen Ausstellungskatalogen sowie dem zuletzt 2019 erschienenen Buch „Franz Parts Schule“ nachlesen. In letzterem erfahren wir einiges über sein vielbeachtetes „Museum der Repliken“, das sich in der Schule, in der Part jahrzehntelang sein ungewöhnliches Projekt vorantrieb, bestaunen lässt. Wir erfahren hier auch über seine „Bewegung der Aneignung“ (engl. „An Ongoing Process of Appropriation“) (1), innerhalb derer „Franz Parts künstlerischer Prozess einer ›Passage‹ [gleicht], durch die ein bereits existierendes Werk mitsamt seiner Genealogie hindurchgeht.“ (2) Und die Philosophin Marina Gržinic fragt und antwortet gleichzeitig: „What is the now-time in Part’s work? A Duchampian gesture.“ (3) Franz Part macht keinerlei Geheimnis daraus, dass er einen gewichtigen Teil seiner Inspiration aus dem Werk Marcel Duchamps bezieht, aber durchaus nicht ausschließlich. Florian Steininger, derzeit künstlerischer Leiter der Kunsthalle Krems, hat den seriellen Charakter im Werk Franz Parts herausgearbeitet: „Seit den 70er Jahren nimmt das Arbeiten in Serien die bestimmende Konstante in Franz Parts künstlerischem Gestalten ein: Das Zyklische, um zu experimentieren, den Weg zu bestreiten, um zu unterschiedlichen Zielen und Ergebnissen zu gelangen, oder einfach die Absicht, ein Thema, ein Sujet oder eine Idee zu variieren.“ (4) Steininger verweist außerdem auf die Beschäftigung Parts mit dessen eigenen Kinderkritzeleien sowie die Auseinandersetzung des Künstlers mit der Art Brut und Jean Dubuffet sowie seinen „Dada-Kontext formaler, medialer und inhaltlicher Natur“ (5) in den 1970er Jahren. Die in dieser Ausstellung teilweise erstmals gezeigten Monotypien Franz Parts, die in den Jahren zwischen 1978 und 1982 entstanden, lassen sich perfekt in den von Steininger aufgezeigten Kontext einordnen: sie sind spielerisch, experimentell, seriell und an Kinderzeichnungen sowie der Art Brut orientiert. Darüber hinaus setzen sie ein Experiment fort, dass sich ursprünglich den Anfängen der Moderne zuordnen lässt, später aber keine weitere Beachtung erfuhr. Interessant und bisher nicht beschrieben in Parts Werk ist das technische Interesse des Künstlers an einer speziellen Form der Monotypie (also einem Druck, der technikbedingt zumeist in einem einzigen Exemplar vorliegt), die man auch unter dem Begriff „Durchdruckzeichnung“ (engl. "transfer drawing" oder "oil transfer drawing") kennt. Nur wenige Künstler vor Franz Part haben diese Technik angewandt, darunter allerdings solch Schwergewichte wie Paul Gauguin oder Paul Klee (auf den sich Part expressis verbis bezieht). Dabei haben andere Bezeichnungen für die Technik wie „Ölfarbzeichnung“ (Klee) oder „gedruckte Zeichnung“ (Gauguin) den Entstehungsprozess eher verdunkelt als erhellt. In der Regel entsteht eine klassische Monotypie so, dass man auf eine Matrize aus Glas, Metall oder Kunststoff zeichnet oder malt, und dann die noch feuchte Farbe entweder manuell oder mit Hilfe einer Druckerpresse auf ein Papier abklatscht. So haben z.B. Auguste Renoir oder Edgar Degas gearbeitet (und Hebert Brandl tut es noch heute), wobei ein zweiter, viel blasserer Abklatsch meist mit einem anderen Medium (z.B. Pastell) überarbeitet wurde. Diese Verfahren ist allerdings viel älter als das Verfahren der noch zu erläuternden Durchdruckzeichnung, gibt es dafür doch schon Beispiele aus dem 17. Jahrhundert, z.B. von Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione. Laut Richard S. Field können bei Gauguin aber „weder seine Mittel noch seine Absicht auf den Kontakt mit anderen Künstlern zurückgeführt werden.“ (6) Die Durchdruckzeichnung kann also als ein genuines Verfahren der Moderne bezeichnet werden, an dem die Rezeption der Moderne aber mit wenigen Ausnahmen achtlos vorbeiging (7). Wie entsteht nun also eine Durchdruckzeichnung bei Franz Part, der sich dabei offenbar von der Vorgangsweise Paul Klees, einem anderen großen Pädagogen, inspirieren ließ? Es gibt dabei verschiedene Varianten: Die Grundform besteht darin, dass eine Glasplatte entweder mit Pinsel oder Walze mit Ölfarbe eingefärbt wird. Dann wird ein Blatt Papier auf diese Platte gelegt und auf der dem Betrachter zugewandten Seite gezeichnet. Hebt man das Papier von der Platte ab, hat sich die Farbe und damit die Zeichnung durch den Druck des Zeichenstiftes auf das Papier übertragen, wobei es entweder dem Zufall überlassen werden kann, welche Stellen durch die Berührung des Papiers mit der Farbe noch mitdrucken, oder ob durch gezielte Bewegungen, die denen beim Abzug eines klassischen Reiberdruckes ähneln, Farbspuren von der Platte auf das Papier übertragen werden. Die gedruckte Zeichnung erscheint nach dem Abziehen des Papiers von der Platte seitenverkehrt (die seitenrichtige Originalzeichnung befindet sich dann auf der Verso-Seite des Blattes). Es handelt sich also um ein Kombinationsverfahren aus Zeichnung und Druckgrafik. Will man eine im Druck seitenrichtige Zeichnung erhalten, dann wird ein Transparentpapier mit Ölfarbe bestrichen, mit der Farbseite nach unten auf ein Blatt Papier gelegt, und die Zeichnung auf der dem Betrachter zugewandten (also der nicht eingefärbten) Seite angebracht. Durch den Druck des Stiftes, überträgt sich die Farbe wie bei einem Durchschlagpapier auf das untenliegende Blatt. Auch hier können durch zusätzlichen Druck flächige Partien angelegt werden. Bei beiden Varianten entsteht eine Zeichnung dunkel auf hell (von uns „Positivverfahren“ genannt). Bei einer dritten Variante, die wir als "Negativverfahren" bezeichnen, wird die Durchdruckzeichnung zunächst wie oben beschrieben angefertigt. Durch den Druck des Stifts auf das Papier wird die Farbe von der Platte auf das Papier übertragen. Auf der Platte wird die Zeichnung als Negativ sichtbar. Wenn ein weiterer Abzug von der Platte in diesem Zustand gemacht wird, erscheint die Zeichnung auch auf dem neuen Abzug als Negativ, und zwar seitenverkehrt und hell (=Papierton). Sollte der Leser das bisher Geschriebene schon reichlich kompliziert finden (Druckgrafik ist nun mal so!), so sei ihm gesagt, dass es weder bei Gauguin noch bei Klee noch bei Franz Part in den meisten Fällen bei diesem eigentlich recht simplen Verfahren bleibt, bei dem - abgesehen von der bewusst übertragenen linearen Zeichnung - vieles dem Zufall überlassen ist. Denn erstens ist es natürlich möglich, eine Durchdruckzeichnung durch mehrere Zeichen- und Druckdurchgänge mit verschiedenen Farben mehrfarbig zu gestalten. Franz Part hat darüber hinaus die Recto-Seiten auch ganz oft nachträglich aquarelliert, wobei durch die Abstoßung von Wasserfarbe und Ölfarbe nicht nur weitere Zufallseffekte (wie z.B. kleine „Lichthöfe“) entstehen, sondern sich die lineare Zeichnung – ähnlich wie im japanischen Farbholzschnitt – in einen sehr malerischen Gesamteffekt einfügt. Der eingangs zitierte Begriff des „Ongoing Process of Appropriation“ lässt sich also nicht nur auf die höchst persönliche Rezeption der Kunstgeschichte von Franz Part, die sich nebenbei bemerkt auch in seiner Tätigkeit als Sammler ausdrückt, sondern auch auf Parts spielerischen und sehr experimentierfreudigen Umgang mit den technischen Möglichkeiten von Kunst anwenden. (1) Ilse Lafer: Eine Bewegung der Aneignung, in: Michael Part /Constanze Schweiger (Hrsg.): Franz Parts Schule; Wien 2019, S. 72-82 (2) Siehe vorige Fußnote, S. 77 (3) Marina Gržinic: A Materialist Turn in Art Education, in: Michael Part /Constanze Schweiger (Hrsg.): Franz Parts Schule; Wien 2019, S. 61 (4) Florian Steininger: Franz Part – Bezugnehmend auf M.D., in: Mathias F. Müller (Hrsg.): Franz Part. Serien und mehrteilige Arbeiten, Waidhofen an der Thaya 2001, S. 5 (5) Siehe vorige Fußnote, S. 6 (6) Zitiert nach: Erika Mosier: Gauguins technische Experimente in Holzschnitt und in Durchdruckzeichnungen in Öl, in: Starr Figura: Gauguin – Metamorphosen, New York/Ostfildern 2014, S. 66 (7) Das deutsche Wort „Durchdruckzeichnung“ (engl. oil transfer drawing) geht möglichweise auf einen Artikel der Kunsthistorikerin Erika Tietze-Conrat in den „Graphischen Künsten“ von 1928 zurück. Erika Tietze Conrad: Ein neues graphisches Verfahren, in: Gesellschaft für Vervielfältigende Kunst [Hrsg.]: Die Graphischen Künste, Bd. 51, Wien 1928, S. 31-32 |

||

|

|

||

|

Franz Part (*1949 in Vienna): Studied at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. From 1975 to 2014, he taught at the Waidhofen an der Thaya secondary school. There, from the end of the 1980s, much acclaimed implementation of the "Museum of Replicas" together with his students (book documentation: Michael Part/Constanze Schweiger (eds.), Franz Parts Schule, Vienna 2019). Since 1989 member and from 1993 to 2004 president of the Galerie Stadtpark, Krems. Exhibitions at Galerie Gabriel, Vienna; Forum Stadtpark, Graz; Neue Galerie Vienna; Landesgalerie Linz; Schneiderei Vienna; Skulpturinstitut, University of Applied Arts Vienna; Ausstellungsbrücke, St. Pölten, among others. Since 2016 artistic director of RAUMFÜRKUNSTIMLINDENHOF, Raabs/Thaya. Part lives in Raabs/Thaya. Part makes no secret of the fact that he is inspired to a great extent but not exclusively by the work of Marcel Duchamp. Florian Steininger, currently artistic director of Kunsthalle Krems, has identified the serial nature of Part’s work: “Since the 1970s, series have been the defining constant in Part’s artistic creativity: the cyclical component, so as to experiment, to embark on a particular path to achieve different goals and results or simply the aim of varying a theme, a subject or an idea.”(11) Steininger also mentions Part’s preoccupation with his own childhood doodles, his examination of Art Brut and Jean Dubuffet, and his “Dadaist context of form, medium and content”(12) in the 1970s. Part’s monotypes, created between 1978 and 1982 and being shown in some cases for the first time in this exhibition, are typical of the context described by Steininger. They are playful, experimental, serial and oriented towards children’s drawings and Art Brut. In addition, they continue an experiment that dates back to the beginnings of Modernism but subsequently attracted little attention. One feature of particular note that has not been written about to date is Part’s technical interest in a special form of monotype, a technique that produces a unique print, also known as “oil transfer drawing”. Before Part, the technique was used by only a few artists, albeit including such heavyweights as Paul Gauguin and Paul Klee (whom Part explicitly mentions). Other names for the technique such as “Ölfarbzeichnung” (oil paint drawing – Klee) or “dessin-empreinte” (printed drawing – Gauguin) have obscured rather than illuminated the process. A classic monotype is normally produced by drawing or painting on a matrix made of glass, metal or synthetic material and then pressing the matrix onto paper manually or with a printing press. This is how Auguste Renoir and Edgar Degas worked and how Herbert Brandl still works today. The technique allows at most a second, then much paler impression, which is occasionally reworked with another medium such as pastel. This process is much older than oil transfer drawing, and examples of it can be found as far back as the seventeenth century, for example by Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione. However, Richard S. Field states that “Gauguin developed his own procedures and […] neither his means nor his ends can be traced to contacts with other artists.”(13) Oil transfer drawing can thus be described as an authentic Modernist process, but one that has been largely ignored in appreciations of Modernism.(14) How does Part create his oil transfer drawings, which are evidently inspired by the process employed by Klee, another great educator? There are several variants. In the basic version, a glass plate is covered with oil paint using a brush or roller. Then a piece of paper is laid on this plate and the drawing made on the side of the paper facing the viewer. The paint and hence the drawing are transferred to the paper through the pressure of the pen. It can be left to chance what else apart from the drawing is printed through the contact of the paper with the paint, or else traces of paint can be transferred from the plate to the paper through deliberate movements as with classic hand printing. After the paper is removed from the plate, the printed drawing is laterally inverted, with the original drawing now on the verso. The process is thus a combination of drawing and printing. To obtain a non-mirrored print, a piece of tracing paper is coated with oil paint, the paint side placed against a sheet of paper and the drawing made on the top unpainted side. Through pressure, the paint is transferred to the sheet underneath, as with carbon paper. Here too, additional pressure can be used to create larger areas. Both variants produce a dark-on-light drawing, which we call a “positive process”. With a third variant, which we call a “negative process”, the transfer drawing is first made as described above. The pressure of the pen on the paper transfers the paint from the plate to the paper. On the plate, the drawing becomes visible as a negative. If another impression is made from the plate in this state, the drawing also appears as a negative on the new impression, mirrored and light on dark (=paper tone). This probably sounds quite complicated – but in printmaking, some things sound more complicated than they are. It should be pointed out, however, that in most cases Gauguin, Klee and Part did not confine themselves to what is actually a relatively simple process in which, apart from deliberately transferred line drawings, much is left to chance. It is possible, first of all, to produce a multi-coloured work by repeating the drawing and printing process with different colours. Franz Part also often coloured the recto sides with watercolour paint. The immiscibility of watercolour and oil paint not only produces further random effects – small “halos”, for example – but also introduces a very painterly overall effect in the line drawing, similar to Japanese colour woodcuts. The term “ongoing process of appropriation” mentioned earlier can therefore be applied not only to Franz Part’s highly subjective attitude to art history, which is also reflected, by the way, in his activity as a collector, but also to his playful and highly experimental approach to the technical possibilities of art. (8) Ilse Lafer, “An Ongoing Process of Appropriation”, in Michael Part/Constanze Schweiger, eds., Franz Parts Schule (Vienna, 2019), pp. 78–82. (9) Ibid., p. 81. (10) Marina Gržinic, “A Materialist Turn in Art Education”, in Part et al., Schule, p. 61. (11) Florian Steininger “Franz Part – Bezugnehmend auf M.D.”, in Mathias F. Müller, ed., Franz Part: Serien und mehrteilige Arbeiten (Waidhofen an der Thaya, 2001), p. 5. (12) Ibid., p. 6. (13) Richard S. Field, Paul Gauguin: Monotypes (Philadelphia, 1973), p. 12 (14) The German word “Durchdruckzeichnung” (Engl. “oil transfer drawing”) was possibly first used by the art historian Erika Tietze-Contrat in an article entitled “Ein neues graphisches Verfahren” in Gesellschaft für Vervielfältigende Kunst, ed., Die Graphischen Künste, vol. 51 (Vienna, 1928), pp. 31–32. |

||

|

|

||