| relief prints/artists a - z |

| prints/other techniques |

| artists' portfolios |

| illustrated books/artists a - z |

| art journals |

| ephemera |

| printing plates |

| 3D objects |

| young art |

| new acquisitions |

|

nd

GENERATION

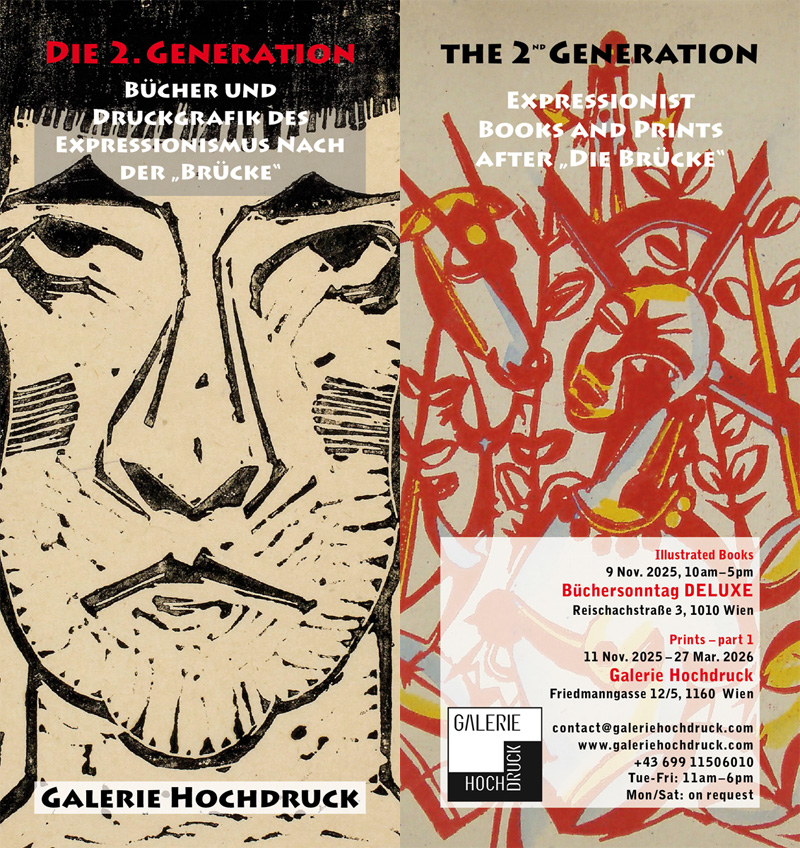

Expressionist books and prints after Die Brücke 11 November 2025 - 27 March 2026 |

|

What else is there to say about (German) Expressionist graphic art that has not already been said? In Vienna – where many art lovers are more familiar with the names Jungnickel, Laske, Kalvach or Walde than with Kirchner, Bleyl, Heckel and Schmidt-Rottluff – probably quite a lot. The latter combined as young students in Dresden in 1905 to form the Brücke artists’ group, which later also included Max Pechstein, Otto Mueller and Emil Nolde. In the spring of 1913, they split up again in Berlin – the circumstances can be read about in any serious history of twentieth-century art – after revolutionising (not only) German art. German Expressionism, as it became known, ultimately entered the world stage as the most important, enduring and far-reaching German contribution to twentieth-century art. The first members of Die Brücke quickly abandoned their architecture studies to become painters and especially graphic artists. They were all outstanding printmakers: in addition to individual works, their prints were compiled into portfolios, and exhibition catalogues were illustrated with high-quality original prints. This repertoire, expanded to include illustrated books, served as inspiration for subsequent artists, until Nazi brutality brought an abrupt end to a progression lasting almost thirty years. Why divide it into ‘Brücke’ and ‘post-Brücke’? The Expressionism of the Brücke period was both a pioneering era and a heyday. Despite individual artistic idiosyncrasies, the graphic production of the main artists is characterised by a rare uniformity, especially in terms of quality. The ecstasy commonly associated with Expressionism is rarely found in the graphic art of the Brücke artists, however. Rather, they drew their inspiration from the natural surroundings of the Moritzburg lakes, where they would go skinny dipping with their models. The scene was dominated by a cheerful insouciance and not yet by the heaviness, pathos and exaltation of the coming war years. The heroes of the Brücke artists were Van Gogh, Gauguin, Vallotton, Munch, German Gothic art, Japanese woodcut artists and the so-called ‘Primitives’. Then came 1914, a year after the group disbanded, which marked a turning point as significant as 1933, albeit with different implications. Pechstein had to flee the paradise of the Palau Islands in the Pacific because of the approaching Japanese, the Russian émigrés in Munich (Der Blauer Reiter!) suddenly became enemies, not to mention Paris, the former international art mecca, which became terra non grata for many foreign artists. After 1913, the individual Brücke members went their separate ways, prompted by the group’s move to Berlin in 1911, and the unifying Brücke style of the Dresden years gave way to more individual and ‘urban’ stylistic developments. In 1917, Kirchner, a morphine addict, left for Switzerland for good. The shock of the years 1914–18 and the immediate post-war years – the horrors of war, hardship, personal loss, hunger, the severing of friendships, but also the feeling of powerlessness in the face of war profiteers – led many of the artists who were initially inspired by the achievements of the Brücke to develop a style expressing consternation, empathy, accusation and agitation, to the point of exaltation, sometimes even bitter sarcasm. Käthe Kollwitz, Otto Dix, George Grosz and Frans Masereel were typical examples of this development. The former Brücke artist Erich Heckel no longer carved nudes in wood, but instead depicted the wounded at the front in Flanders. And the etching Hashish III by the Austrian Ludwig Wachlmeier, alias Aloys Wach, created in Paris shortly before the outbreak of war, recalls the helpless desperation of Georg Trakl’s last poem ‘Grodek’ from the first year of the war. Shortly after writing it, Trakl ended his life at the age of twenty-seven through an overdose of cocaine. ‘All roads lead to black decay.’ Of course, Wach could not have known Trakl’s ‘Grodek’ at the time, and might not even have heard of the poet at all, but it is the similar approach and processing of their experiences that make both of them outstanding exponents of Expressionism. Christian Rohlfs’ woodcuts occupy a special place in German Expressionist printmaking. He was born in 1849 as a child of German Romanticism and became an important representative of Impressionism towards the end of the nineteenth century and something of a father figure to the Brücke artists. He was apparently so impressed by the work of this artists’ group that for several years after 1910, when he was already sixty-one years of age, his own distinctive stylistic experiments showed Expressionist influences. The scientific and social upheavals around 1900 provided fertile ground for various secessionist movements and, later on, for Expressionism. After the Brücke, however, this art movement was influenced not only by the personal impact of the war, but also by two other trends: first, the gradual integration and assimilation of styles from outside, especially Futurism and Cubism and then later also New Objectivity; and second, a marked politicisation. The Dadaist Hans Arp mocked Expressionism in 1924 as ‘minced meat’, a ‘metaphysical German beefsteak ground with a mixture of Cubism and Futurism’. As is often the case, this wry observation contained a grain of truth. It almost sounds as if Arp regretted that Expressionism had lost the naivety of its Brücke beginnings. In fact, after 1918, Expressionism in Germany, like the economic situation, turned into an inflationary phenomenon with a certain eclecticism. Angered by the rejection of Paul Cassirer and Paul Westheim in Berlin in 1920, Carry Hauser, an Austrian Expressionist and member of the Passau Fels Group, remarked: ‘In Berlin, if your forms are not coldly brutal and angular, you are mawkishly Viennese. What is now called art in Berlin is Viennese arts and crafts from 1910, only much more tasteless, superficial and cloaked in intellectual pretension. At least we openly called it ornamental back then; in Berlin, they call it mystically expressionistic." The Novembergruppe, founded in Berlin at the end of 1918 and inspired by the sailors’ revolt in Kiel in 1918 – the ‘November Revolution’ heralding the end of the First World War – was highly inclusive. In contrast to the more exclusive Brücke artists’ group, over 480 artists were associated with it, and it was characterised by a corresponding diversity of styles. Its motto was political. The founding manifesto stated: ‘We stand on the fertile ground of revolution. Our slogan is liberty, equality, fraternity.’ The direct reference to the French revolutionary motto was clearly provocative. The initiators included Max Pechstein, Georg Tappert, César Klein, Moriz Melzer and Heinrich Richter-Berlin. Pechstein drew the symbolic torchbearer with a burning heart on the cover of the brochure ‘To All Artists!’, which called for the participation of artists in future cultural policy. After the end of the First World War, Expressionism also spread rapidly to other countries, with cells from Tartu to Belgrade, and from Zurich to Moscow, where stylistic elements of Expressionism featured prominently in film. It arrived somewhat later, in the late 1920s, in the USA but with impressive chiaroscuro effects, particularly in the new graphic novel medium. The French-speaking world was the only place where Expressionism never really took off, with the exception of Frans Masereel, who was in fact Flemish. As early as 1910, politically charged Expressionism was present in German magazines such as Herwarth Walden’s legendary Der Sturm, but even more so in Franz Pfemfert’s Die Aktion. In addition to their literary and political content, these magazines, published continuously during the period of the Weimar Republic, provide important documentation of art trends of the time. The publication of graphic art on the front pages of Der Sturm began with provocative Expressionist drawings by the young Oskar Kokoschka, continued with original woodcuts by the Brücke artists and their successors, and ended in the 1930s with Constructivist graphic art. This brings us to Austria’s contribution to Expressionist printmaking. Compared to Germany, there is actually very little to report here. In Vienna, Kokoschka, a young teacher, was declared unacceptable by the authorities and dismissed. He first achieved success through the mediation of Adolf Loos via Herwarth Walden’s Sturm Gallery and Paul Cassirer in Berlin, and later also internationally. Austria’s most important Expressionist, Egon Schiele, contributed little to Expressionist printmaking apart from a handful of prints that owe their creation to external circumstances. Richard Gerstl, who committed suicide at the age of twenty-five in 1908, did not leave any prints. Then there was Alfred Kubin, who was associated with the Blauer Reiter in Munich and occupies a special position as a symbolist and fantasist, Max Oppenheimer, whom Kokoschka accused of plagiarism, the aforementioned Aloys Wach, Georg Ehrlich, Wilhelm Traeger and, primarily as book illustrators, Erwin Lang and Uriel Birnbaum. Other artists, a generation younger than the founders of Die Brücke, jumped on the Expressionist bandwagon after the First World War. They include the printmakers Otto Rudolf Schatz, Carry Hauser, Karl Rössing and the wonderful Margarete Hamerschlag, who never really found her way into the market because her Expressionist woodcuts from the interwar period have only been preserved in trial or unique prints and are correspondingly rare. At all events, the claim that Expressionism came to an end with the outbreak of the First World War (as stated on Wien Wiki) is difficult to understand. Even late in the twentieth century, artists such as Erich Steininger and Klaus Süß clearly drew on early figurative Expressionism, and Hans Hartung’s wildly gestural informal woodcuts in the 1970s, some hacked with an axe, form a link with one of the first significant prints of Abstract Expressionism, Kurt Schwitters’ untitled woodcut for Erich Küppers’ Kestnerbuch in 1919. |

|

SUMMER 2025 Click here to view the online catalogue |

|

|

| The nude, the representation of the naked human body, began its existence as a ritual object in the form of pictures and sculptures, while its German name 'Akt' originally referred to the study of the body in motion. Today, the classic artistic nude is increasingly perverted through the immeasurable flood of pornographic images. This has led to a new kind of prudery, in which even the slightest interest in nudes, however artistically or historical significant they may be, becomes suspicious. Facebook and Instagram have set the standard for this new prudery, going as far as classifying the Venus of Willendorf as pornographic. In between there were the well-known nude art scandals of the nineteenth century involving artists such as Manet, Goya, and Courbet. They dwindle into insignificance, of course, compared with everything that is generally expected of and tolerated today in mainstream cinema and theatre.

In fact, the real and much less showy platform for the classical nude is drawing, from rapid sketches to detailed studies, on their own or as preparation for a larger work in another medium. Although we are talking about drawings here, prints are related to them to a certain extent. Either preparatory drafts are made during the production process as was the case with Käthe Kollwitz's woodcuts, or the drawing is applied directly to the printing matrix, as with etchings or lithographs. The German Expressionists even carved the image with a knife directly onto the woodblock. Unlike some studies drawn on paper, prints – not mechanically reproduced images – are always to be understood as stand-alone works of art, since they are rarely intended for transfer to another medium. Photography is a special case. Although chemical analogue photography is not a print-making technique, a survey of the history of nude pictures would not be complete without consideration of this medium, not least as it was used from early on to provide artists with nude models. Moreover, for large print runs, photographs had often to be converted into a stable printable medium, such as photogravure, collotype, relief halftone, rotogravure or the more recent giclée print, not to mention the many possibilities for using photographic templates in screen printing or other printable media. The exhibition at Galerie Hochdruck brings together printed and drawn nudes over a period of five hundred years – from Dürer's ironic and probably autobiographical Men's Bath House (c. 1497) and mythological or Old Testament depictions such as Hans Sebald Beham's Joseph and Potiphar's Wife (1544), whose small format inevitably brings to mind historical carte-de-visite nude photos, to the vulnerability of the human body in Käthe Kollwitz's disturbing depictions, Anton Kolig's hastily drawn male torsos, and the humorous (self-)portraits by Kia Sciarrone, a photographer and the youngest participant in the exhibition. |